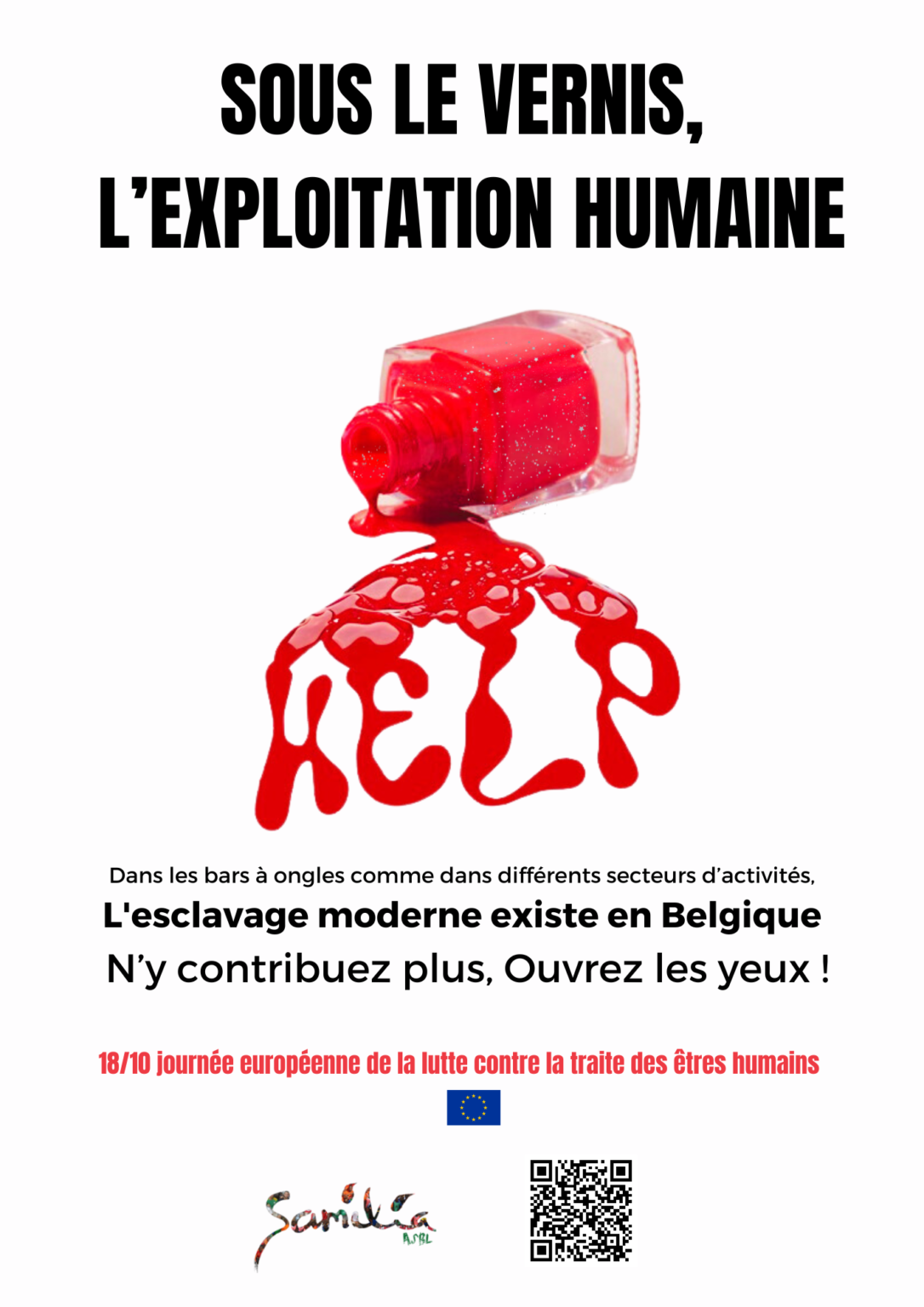

The reality of the living and working conditions of workers who are victims of this modern-day slavery is far darker:

– Working conditions do not always comply with regulations: corrosive and flammable products are sometimes stored in large, unsecured containers.

– Workers without legal residency status are particularly vulnerable: the shop owner knows they can demand a higher cut of the worker’s services—often 75% (sometimes 50%) of the amount paid.

– In the end, the worker is not paid decently for their labour. After covering the cost of tools and products, the owner’s percentage for each service, and the rent, the worker still has to repay the debt of their journey and support their family back home.

– Workers are often housed by the nail bar owner, who also provides them with food. This creates complete control and opens the door to abuse. To be more “profitable,” the worker is often required to look after the owner’s children as well. In some cases, they are subjected to psychological, physical and/or sexual violence.

– Workers must repay a travel debt (which may amount to €15,000 or more) and remain under the traffickers’ control for many years. If they fail to pay this debt, their families back home may also be threatened.

Testimonies

Lola:

“I ended up with an Asian man who didn’t speak a word of French. He tapped my hands and pointed at things so I could respond to his silent requests. I wasn’t even sure he had understood what I wanted or whether the final result would match my expectations.

He was dressed very poorly, as if wearing basic second-hand clothes. He completed my acrylic nails in a record 30 minutes, and even the shop owner was so stunned that she asked to inspect my nails to check that they were done properly. During the treatment, he regularly received remarks in his native language from the nail bar manager. I wasn’t injured during the session, but personally I will not go back because the exploitation is too obvious.”

Alice:

“While walking through a shopping gallery in the centre of Brussels, I came across a large number of neighbouring nail bars and decided to try one because the prices were so attractive. There are usually between 3 and 5 technicians per ‘nail shop’, and roughly as many women as men, all Vietnamese. It was a Wednesday late afternoon and some bars had queues extending outside. For others, workers were waiting outside to approach and entice clients.

I clearly hesitated because the lack of ventilation and the overwhelming smell in the hallway immediately gave me a headache. I finally entered one of the nail bars, hoping I could bear the smell long enough for a manicure. Two young students had just finished. One woman spoke good French and shared her workspace with a man who only spoke his native language.

The woman seemed very stressed as soon as a new customer arrived, because she had just begun working on me. Her stress was obvious in her rushed movements and breathing—she clearly feared that the new client, who seemed to be a regular, would lose patience and leave. In her haste, she injured me while filing. The manager was willing to work beyond opening hours (she gave me her card and suggested I could make appointments on Saturdays and Sundays with no time limits, implicitly).”

The Role of the Labour Prosecutor (Auditorat)

Human trafficking can take several forms: sexual or economic exploitation, forced begging, organ trafficking, and forcing someone to commit a crime or offence. Human trafficking is a crime linked to transnational organised crime.

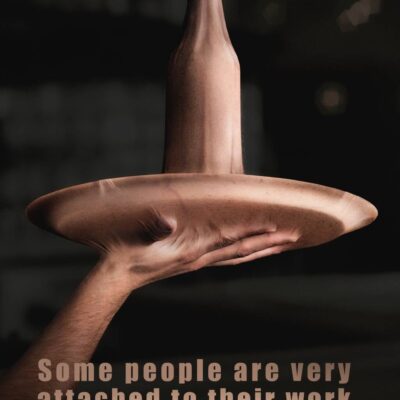

Trafficking for economic exploitation differs from illegal employment of foreign workers in that the trafficking victim is forced to work in conditions that violate human dignity and does not receive a decent wage. It occurs in many sectors: construction, agriculture, garment production, road transport, football, cleaning services, hospitality, car washes… and nail salons. In cases of human trafficking for economic exploitation, labour courts have jurisdiction.

In this context, the Labour Prosecutor’s Office carries out the public prosecutor’s functions when citizens’ rights regarding social security are at stake, as well as in cases of violations of social criminal law, acting against offenders.

At the Brussels Labour Prosecutor’s Office, the phenomenon of nail bars operated by people of non-European origin is considered worrying, growing in scale, and expanding geographically. It is also one of the priorities of the SIRS (Social Information and Investigation Service).

These cases are difficult to investigate due to complex cultural dynamics and require time and resources. Bringing such cases to court requires coordination between several actors: the Regional Labour Inspectorate, the National Social Security Office (ONSS), and the Police.

Since 2018–2019, social inspectors have begun focusing on this phenomenon, which intensified during COVID. They collected data that helped describe the modus operandi: traffickers, generally operating from Southeast Asian countries, exploit their victims during their migration route to the UK by forcing them to work in nail bars. Belgium appears to be a preferred destination for these traffickers, who may also use nail salon activity as a front for other illegal practices, such as money laundering.